Unfortunately, most horses suffer from a bout of lameness at some point in their lives. While the cause of lameness may be obvious, such as a foot abscess, corn or bruised sole, sometimes lameness can result from more complicated disorders.

Any lame horse requires a logical and thorough approach in order to accurately work out the cause of the lameness, so that an appropriate treatment plan can be devised.

A general physical examination is usually performed first and after this, attention is directed towards assessing the limb(s), which may be affected. This is referred to as a static assessment. During static assessment, limb conformation, foot symmetry and shoe placement are assessed. Then hoof temperature, digital pulses, joints, tendons and ligaments are palpated for heat, pain and/or swelling. Static flexion of the joints is usually performed at this point too. At this time hoof testers may also be used, or it may be the vet’s preference to use these after walking and trotting has been performed. In some cases, the cause of lameness is immediately obvious. However, following a basic examination of the suspect limb(s), the vet then needs to confirm/identify which limb(s) are affected.

How is lameness spotted?

You will be asked to walk the horse away and back to begin with (dynamic assessment). This allows for the vet to spot whether or not the lameness is obvious at walk.

The easy way to assess a lameness is to watch the horse’s gluteal muscles (rump) as it walks away, an obvious drop or hip hike on one side identifies that as being the lame limb. Watching the horse walking towards you is the best time to try to spot forelimb lameness. When the horse is walking toward you it will nod its head down on the sound leg, and lift the head up on the lame leg. Trying to spot lameness at walk can be difficult in all but moderate to severe lamenesses. As such it is often necessary to assess the horse while trotting in a straight line.

Occasionally it may be necessary to lunge the horse on both a soft and a hard surface in order to try to work out which limb(s) are lame.

Flexion Tests

Once the lame leg has been identified, flexion tests are usually then performed. These are designed to place stress on the joints. The theory behind flexion tests is that they may exacerbate the lameness, thereby helping isolate the seat of pain. However, flexion tests don’t always tell the truth and this is why further, more sensitive and specific, diagnostic tests are then performed as part of the lameness investigation.

Once the lame leg has been identified, flexion tests are usually then performed. These are designed to place stress on the joints. The theory behind flexion tests is that they may exacerbate the lameness, thereby helping isolate the seat of pain. However, flexion tests don’t always tell the truth and this is why further, more sensitive and specific, diagnostic tests are then performed as part of the lameness investigation.

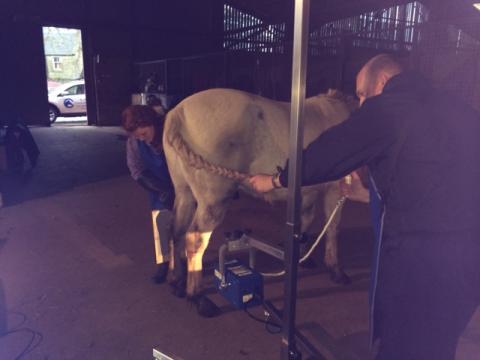

Picture 1: Flexion tests being performed as part of a lameness investigation.

Perineural Anaesthesia (Nerve Blocks)

Nerve blocks are the next logical step in the lameness investigation. Nerve blocks involve injecting a small amount of local anaesthetic around the nerves supplying sensation to certain areas of the leg. Usually nerve blocks are started at the bottom of the leg and are performed in sequential order up the leg until the horse goes sound. This helps to isolate the area of pain more accurately. In turn this allows the vet to focus attention on the structures that are innervated by a particular nerve e.g. a particular joint, tendon, ligament etc.

Intra-articular Anaesthesia (joint block)

Often this is the next step to be performed after nerve blocks. (However, you have to wait for the nerve block to wear off to accurately assess joint blocks). Joint blocks involve the direct injection of local anaesthetic into the joint. If the problem area involves the joint e.g. as in a case of osteoarthritis, then the horse should become sound around 10 minutes or so post injection.

Radiographs (X-rays)

Once the seat of pain has been isolated, radiographs are usually taken of the affected region. These are particularly useful for assessing boney abnormalities e.g. cases of osteoarthritis, fractures etc.

|

|

| Picture 2: Radiographs been taken with our portable X-ray machine |

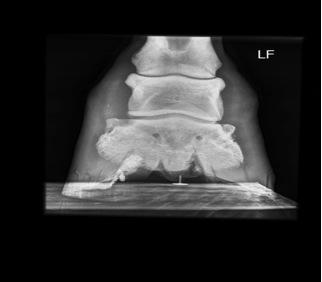

Picture 3: Radiograph of a horse's foot being assessed for mediolateral imbalance |

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is also frequently used in lameness investigations and is most commonly used to assess potential damage to soft tissue structures such as ligaments and tendons.

Nuclear Scintigraphy (Bone scan)

Nuclear scintigraphy, also known as a bone scan, is an advanced screening technique used to locate areas of increased metabolic activity in soft tissue or bone, which may indicate a site of injury. Bone scanning allows an image of the entire horse to be obtained. This can be very useful in cases of subtle lameness, where an exact source of pain has proved difficult or even impossible to identify through nerve blocks. The horse is injected with a radioisotope (Technetium – 99) that is absorbed in increased amounts in regions of the body undergoing metabolic remodeling processes e.g. bone following an injury. Using a gamma camera, any areas of increased uptake can be identified and pursued further with other diagnostic techniques.

Nuclear scintigraphy is particularly useful to image areas that are difficult to assess with other imaging modalities, such as the back, pelvis and upper limbs.

Nuclear scintigraphy can also be used to detect problem areas, which may not be readily apparent on radiographs – such as stress fractures and ligament injuries. It can also assist in diagnosis of horses with multiple sites of pain. It is important to remember that nuclear scintigraphy is a more specialist diagnostic technique, which involves referral to an equine hospital that possesses the necessary equipment. Nuclear scintigraphy does not replace other diagnostic tools such as radiographs or ultrasound, and it should be regarded as an ancillary diagnostic technique for the more challenging case.

Magnet Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is a relatively new and highly specialist imaging technique and it is an imaging modality only offered by a few referral hospitals in the UK. It is often the final diagnostic technique to be used in problem cases.

MRI involves placing the part of the body to be imaged (often a foot or lower limb) inside a strong magnetic field. Radio wave pulses are then applied to the area and a radio wave signal is generated and then received by a computer. The computer subsequently generates an image.

One of the main advantages of MRI is that it allows for both bone and soft tissue structures to be assessed at the same time. Prior to performing MRI the seat of pain must be localised by nerve blocks, so that the area to be scanned is known.

Probably the most common area to be scanned using MRI is the foot. This is because an MRI offers unparalleled imaging of the complex anatomy within this region.